Happy Friday, everybody! We’re back with another edition of the CTEC Newsletter, and this one is jam-packed with excellent analysis and insight from a wide array of researchers.

First up, Senior Project Manager Meghan Rahill gives an overview of one of the stranger groups organizing on the American far right, Super Happy Fun America. Next up, Digital Researcher Enrique Nusi gives you a crash course in how to grab data from Twitter in R and get it into a nice format. Following the coding tutorial, MIIS student Matthew Goldenberg talks about the influence of extremism on Star Wars fandom (and vise versa). CTEC Research Fellow Julie Huynh comes in with a great overview of the recent French anti-Islamism legislation, and then MIIS student Ben Mueller closes us out with a discussion of “doomerism.”

Hope you enjoy it!

Super Happy Fun America: the Right-Wing Protest Movement With Ties to Neo-Nazis

By Senior Project Manager Meghan Rahill and Deputy Director Alex Newhouse

In August 2019, a political organization called Super Happy Fun America organized a so-called “Straight Pride Parade” in Boston. From the moment it was announced, the event drew significant media coverage, controversy, and attention from left-wing activists, many of whom believed that it was a front for a far-right demonstration. In fact, when the parade took place, alongside participants marching with American flags and MAGA apparel, several donned symbols and logos associated with far-right extremist groups. Milo Yiannopolous, a notorious far-right provocateur with deep ties to ethnoseparatists and who once openly supported pedophelia, was the grand marshal of the event.

So what exactly is Super Happy Fun America (SHFA)? The organization is a Massachusetts-based political group which states its support for “defending the constitution, opposing gender madness, and defeating cultural Marxism” [profile not cited to avoid amplification]. They call themselves a “straight-pride” group and are most recognized for their use of memes and flashy events to normalize radical right-wing ideologies.

SHFA claims that their straight pride events seek to assist the “oppressed majority” of straight individuals in a wider effort to fight “heterophobia” in modern society. These baseless and clearly hateful statements alone are alarming, but the group's anti-LGBTQ sentiments are only the tip of the iceberg.

History

Domestic violent extremism in the United States no longer has a clear-cut definition, but the seriousness of SHFA’s extremist ties are clear. While SHFA espouses masked alt-lite sentiments which make it harder to identify the threat, it also has tangible links to explicit domestic extremist movements and groups. Even the origin of the organization is inherently connected to right-wing extremism.

Notorious Proud Boy affiliate, Third Positionist, and neo-Nazi adjacent agitator Kyle Chapman (also known as Based Stickman) is the progenitor of the group that would become known as SHFA. In addition to his acts of violence, Chapman is best known as the founder of two extremist groups: the paramilitary subgroup of the Proud Boys known as the Fraternal Order of the Alt-Knights (FOAK), and the Boston alt-lite group known as Resist Marxism.

Resist Marxism emerged in 2017 primarily as a protest group. Its members, drawn from a wide array of movements across the right-wing spectrum, participated in demonstrations and organized their own events. Chapman often attempted to claim that the group was opposed to white nationalism, but public and leaked evidence from their communications suggest otherwise.

In 2019, Resist Marxism leaders used Telegram to communicate with other organizations and attempted to form the “East Coast Patriot Nomads,” a loose alliance of right-wing extremist groups and networks on the East Coast. The goal was to host larger joint protests with alliance members to spread awareness of their ideology and to grow the movement nationally. During one key protest in Providence, Rhode Island, prominent far-right extremist Alan Swinney attempted to strangle a female counter protester on camera. His actions reflected poorly on Resist Marxism, and his online rhetoric showed continued support for premeditated attacks against counter protesters with little remorse. (Little, 2020).

The incident left Chapman and many others feeling as though Resist Marxism needed to distance itself from such violent actions. In 2019, group infighting over this issue led Resist Marxism to rebrand to Super Happy Fun America.

The Threat From the So-Called “Alt-Lite”

Super Happy Fun America presents itself as part of the “alt-lite” movement. According to the Anti-Defamation League, the term alt-light is a terminology “created by the alt right to differentiate itself from right-wing activists who refused to publicly embrace white supremacist ideology.” The term refers to a loose assortment of individuals and groups who adhere to the core beliefs of the alt-right while dodging explicit association with white supremacist movements or affiliated groups. Many of these individuals espouse racist, anti-semitic, anti-LGBTQ+, anti-immigration, and mysogynistic rhetorics. Individuals within the alt-lite tend to adhere to one or more of these sentiments under the guise of achieving “civic nationalism.”

In theory, civic nationalism, as opposed to racial or ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism which endeavors to create a unified national identity. In the United States, alt-lite groups have hijacked the concept of civic nationalism for their own purposes, using it as a smokescreen to distract from racially charged motives and actions. Alt-lite affiliates avoid using explicitly white supremacist terms and claim to value morals such as: duty and loyalty to one’s own nation, freedom from government, rights of the individual over the collective, and the vague notion of “western ideals.” At the end of the day, this warped facade of civic nationalism, in combination with other alt-lite ideologies, is in essence a repackaging of American white separatism or supremacy.

What is Super Happy Fun America and Why Should We Care?

Super Happy Fun America is a decentralized group of extremists calling themselves “alt-lite” who push a right-wing agenda via in-person protesting and vocal commitment to nonviolence and a “legitimate” transition of power. However, their rhetoric largely appears to be a facade designed to mask more violent, fringe, and even outright accelerationist beliefs. From its name to its public communications, the organization attempts to cast its ideology as palatable via memes and flashy events. Due to this, most of their commentary appears to be light-hearted when it is inherently dangerous.

In addition to the now-notorious Straight Pride Parade in 2019, SHFA played a significant role in anti-lockdown protests toward the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. SHFA president John Hugo, who has spent the last few years committed to spreading anti-LGBTQ propaganda and activism, helped organize a protest in Massachusetts in May 2020. During the demonstration, Hugo deployed rhetoric that included explicit references to revolutionary activity. “My fellow Americans, it is time to rise up. It is time for insurrection,” he said.

Hugo’s statement did not come from out of left field. SHFA has roots and connections to the accelerationist movement, a loose coalition of groups and individuals that crosses ideological lines which aims to usher in apocalyptic social collapse. The most active component of this movement is the community of revolutionary neo-Nazis, with which Kyle Chapman has increasingly associated himself with. In addition, SHFA included among its ranks a man named Chris Hood. In recent years, Hood has been something of a journeyman extremist, hopping from the anti-government Three Percenters to the neofascist group Patriot Front and radical accelerationist network The Base (with a stint in the Proud Boys). Now, Hood runs a neo-Nazi streetfighting group called NSC-131 (or Nationalist Social Club Anti-Communist Action).

Perhaps most notably, NSC-131 has actually served as a security force for SHFA, and their leaders have developed close relations. NSC-131 is primarily active in New England, and the two groups likely share more members than just Hood. A SHFA also expressed admiration for a Base-, NSC-131, and National Socialist Movement-connected accelerationist after he attempted to bomb a hospital in Missouri.

Super Happy Fun America’s ties to accelerationist and fascist groups indicates a much more sinister side to their irony-drenched, meme-ified rhetoric. Groups like this often attempt to use humor and absurdity as a Trojan horse of sorts, aiming to make white supremacist and revolutionary concepts more mainstream. As with most other extremist movements, though, SHFA’s true nature is revealed by its in-person action and the people it associates with.

On January 6, 2021, Super Happy Fun America chartered buses and brought several members into Washington, D.C., in order to protest the election of Joe Biden. They were not mere bystanders in the violence that followed: in line with their recent rhetoric, SHFA members took part in the attempted insurrection against the U.S. government, storming the Capitol alongside Proud Boys, Three Percenters, Oath Keepers, and others.

As SHFA shows definitively, right-wing insurrectionary activity doesn’t always have to come cloaked in Nazi iconography. Sometimes it is also decked out in colorful flags, memes, and irony.

How To: Collect Twitter Data in R

By CTEC Digital Researcher Enrique Nusi

This article assumes a base-level knowledge of R and RStudio (if you’ve had a semester of quantitative methods in R or checked out Hadley Wickham’s excellent R For Data Science, you’re more than qualified). For an install guide and quick refresher, I suggest the following: https://rstudio-education.github.io/hopr/starting.html or R4DS’s guide.

Social media analysis is an important dimension of policy research for which there are an overwhelming number of tools to collect, process, and analyze text data. The state-of-the-art tools often require a high degree of specialist knowledge, while the simplest may either be locked behind a paywall or not work at all as advertised. In this article, I will introduce a powerful tool for creating your own custom data sets in which you can Ctrl-F search of thousands of Tweets instantly. You can also process and analyze the resultant data set further in R with a suite of analytical tools which we’ll cover in the future.

If you know how to run code in RStudio, then this tool is should be no more difficult to use than downloading this short script, changing options as desired, and running the script. The code is presented in Markdown format, so each step of the collection process can be run line by line or in chunks (I will also include a regular .R file for those unfamiliar with Markdown).

For those not familiar, R Markdown allows you to write prose interspersed with code chunks which can be run inside of the doc itself. If you’ve used Python in the past, Jupyter Notebook is very similar to R Markdown. R Markdown is so helpful, in fact, that we can’t recommend strongly enough learning how to code via R Markdown docs: while you’re trying to figure out how to code something, write out prose descriptions of what you’re trying to do.

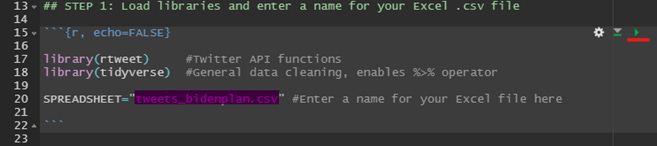

Step 1: If you do not already have them, install the “rtweet” and “tidyverse” packages by running the following in the console:

install.packages("rtweet") install.packages("tidyverse")Enter the name you would like for your eventual final dataset, highlighted in pink below. Run by clicking the green arrow (underlined in red).

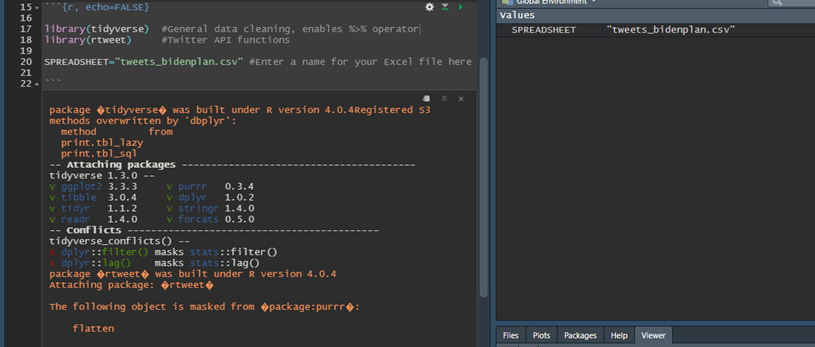

Your environment should look something like this after running. Since President Biden’s infrastructure plan was the top story of the day, I decided to create a dataset built around that, thus I named it tweets_bidenplan.csv for ease of searching later. Don’t worry about any red X’s that show up after running this chunk, it’s just letting you know that tidyverse and rtweet are now running and some functions may behave differently.

Step 2: Make your desired changes to the areas highlighted in pink (and repeat for as many searches as you want). I’ve tried my best to include clear directions for what each parameter does. You can search any hashtag or term by entering it where highlighted, then you can select the number of Tweets you want to collect. If you want re-tweets you can change the FALSE to TRUE and it will include them, and you can choose between collecting the most recent posts or the most popular ones. To select a language, enter the appropriate digraph in the final highlight—to find the appropriate one, see https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/twitter-api/v1/developer-utilities/supported-languages/api-reference/get-help-languages.

You’ll notice that I’ve included multiple search_tweets function calls connected by a “%>%” (pipe) operator and “rbind”. Each search_tweets call creates a new data frame based on its query results, and then rbind pastes them all together into one big data frame. If needed, you can copy and paste the rbind chunks and repeat as many times as needed. Just remove the pipe operator (%>% underlined in orange) from the very last line, then click the green arrow for the STEP 2 chunk.

To run searches on multiple terms, you can also change the query parameter (“q”) to a series of terms separated by an OR operator. For example, if we wanted to look for tweets that mention either #buildbackbetter or #bidenharris, we could change the query to:

q = "#buildbackbetter OR #bidenharris" Boolean operators let you run searches for multiple terms in one search_tweets call, but I use the rbind method to allow for more granular control over the number of tweets to look for.

R will open a new browser window and ask you to log into a Twitter account to authenticate. You do not need to use your personal or professional Twitter account, any random account will work. This part may take anywhere from 30 seconds to 5 minutes to run depending on the number of Tweets collected.

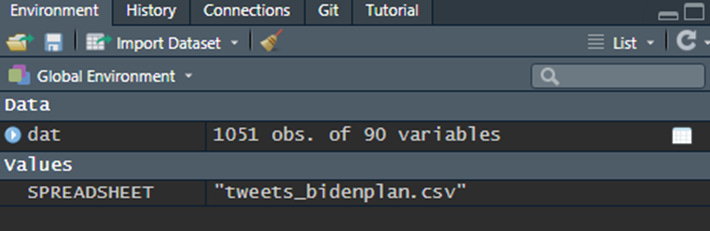

You should now have a data frame called “dat.” You can click on this to view the data before moving on to the next step.

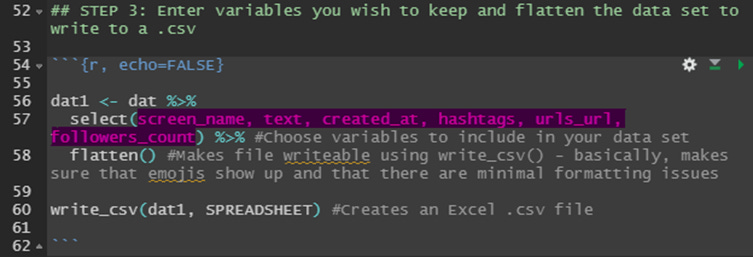

Step 3: The search_tweets function pulls 90 different variables (columns) from the platform from the previous 6 days. Each observation (row) is a single Tweet. Identify the variables you want to keep and enter their names in the “select” function, highlighted in pink. For example, if you just want text data, you may only want screen_name, text, created_at, and hashtags. If you’re a more advanced user looking at network analysis, you can also include retweet_name or country or any other relevant metric. Once you pick your variables, run the chunk and it will automatically generate a .csv that can either be imported into a Google Sheets or a proper Excel file for manual analysis.

FOR GOOGLE SHEETS: The best/easiest way to display your custom data set properly is to create a Google Sheets document and select File > Import > Upload and drag your newly created .csv into the box. You can open the Excel file directly also, but Windows may not display emojis correctly.

FOR EXCEL: If you need to work offline and would prefer a local file, Windows users should create a new Excel file, select Blank Workbook, and then navigate to Data > Get Data > From File > From Text/CSV and then select the .csv you generated; from the File Origin dropdown menu, select the option "65001: Unicode (UTF-8)" and click Load. It should display black-and-white versions of the collected emojis. For full color emojis, the Google Sheets method may be preferable.

The Rise of the True Fan: Hate Groups, Radicalization, and Star Wars

By Matthew Goldenberg, MA Candidate in Nonproliferation and Terrorism Studies at MIIS

It’s just a movie, right? Not if you ask Geeks + Gamers, a YouTube channel that has claimed that fighting over the quality of Star Wars films is a battle akin to a cultural civil war. Since the release of the sequel trilogy, a select group of fans have coalesced into a powerfully toxic community that spreads hate across the internet. This is not the story of those who simply like the films; rather, it is the story of a group who transformed their hatred into a misogynistic campaign that is radicalizing fans through far-right ideology masquerading as film criticism. This is the story of the Fandom Menace.

Monism is the idea that there is only a single correct answer to everything. It is a building block of extremism and has infested the way we consume media. The recent Star Wars films certainly have their detractors, but the Fandom Menace has taken their objections to another level. When they disagreed with plot and character choices in the new films, the monism of some fans caused them to believe that their personal version of fictional space wizards was the only possible correct one. This thought is innocuous in isolation, but extreme elements quickly picked up on it. A male-characters-only cut of The Last Jedi was crafted by members of the community to express their disgust for the women of Star Wars. John Boyega, one of the lead actors of the films and a black man, became the center of a racist boycott campaign. The Fandom Menace proffered that since the films did not correspond to their preferences exactly, it was inherently wrong and evil.

This story matters because it’s not really about Star Wars. These are the same impulses, and often the same people, that drive Gamergate, Men’s Rights Activists, and on the far end of the spectrum, QAnon. Various groups across the internet have begun to identify themselves as the only legitimate fans, believers, adherents, etc. This has resulted in an exclusionist attitude towards any and critics, no matter how minor. Such self-sorting into neat boxes of “us” versus “them” is one of the most basic characteristics of extremist group behavior. The new in-group believes that they possess absolute truth and hurl vile hatred at the dissenting out-group. Pop culture has long been used on occasion as a shibboleth; the Internet has super-charged the weaponization of fandom.

Extremist thinking metastasized in mainstream fandom culture most infamously in 2014. Gamergate began that year, escalating from a jilted lover’s misinformation-laden blog post about his ex-girlfriend into a misogynistic harassment crusade. The original grievance and the campaign’s ostensible goal—to interrogate “ethics in games journalism”—became subsumed in an ideological war over women in games, representation in narratives, and progressivism more broadly. Many of the cultural cudgels honed during Gamergate would be deployed during the right-populist wave of 2015-2018.

Gamergate’s ideology and tactics have been inherited by the Fandom Menace. Like Gamergate, it was kickstarted via the coordinated harassment of a woman. Kelly Marie Tran, a Star Wars actor, left social media after a harassment campaign conducted by fans who placed her as the focal point of their ire against feminism in cinema. An early Fandom Menace YouTuber and leader in the Comicsgate community, Ethan Van Sciver, bought many action figures of Tran’s character and decapitated them for an hour while raving about his hatred of The Last Jedi. Following the mass murder of Asian-American women in Atlanta in March 2021, Van Sciver “joked” during a livestream that “it’ll never stop me from killing Chinese people...give me a Tommy gun and line them up against the wall.” He also contributed to a manual on crafting a so-called Geeker Gate. The handbook enumerates the steps towards harnessing manufactured hatred over pop culture into harassment, conflict, and profit. As this manifesto suggests, members of Gamergate have migrated into the Fandom Menace as they pursue a common path in pushing hate into mainstream geekdom through their respective Geekergates.

Yet these groups go beyond mere hatred to delve into the realm of QAnon-like conspiracy. QAnon theorizes that there is a global cabal of elites who control all media and traffic in pedophilia. Posts circulate on Telegram and Parler featuring news with truly stupefying headlines. One claims that the Pope was executed last February; another suggests that President Biden is actually President Trump in a face mask with CGI, running the country from behind the scenes. Similar conspiratorial framing proliferates with stunning frequency among the Fandom Menace. Dissatisfied fans have been claiming for years that Kathleen Kennedy, the current president of Lucasfilm, has been or will be fired any day now, or that Star Wars is being run from the shadows by two other creators, Jon Favreau and Dave Filoni. Like QAnon influencers, the community posits that they are at the vanguard of identifying a far-ranging conspiracy, for which the top brass at Lucasfilm are targeting them personally. When another article dared to criticize the community recently, the Fandom Menace responded with the language of conspiracy, employing numerology and referring to their critics as part of false flag operations or paid Lucasfilm puppets. Their theories always come from supposed “inside sources”, predicting events that never materialize. Those who they disagree with are branded as being not “true fans.” This key marker of in-group inclusion has emboldened the Fandom Menace. When their influencers are criticized, members display cult-like devotion, moving to attack en masse with doxxing and death threats. Like Gamergate, criticism is perceived as a crisis-level threat from the out-group, and that pushes the collective towards more extreme actions.

The community is turning fan spaces into a war zone that only deals in absolutes of good and evil. This Manichean attitude is appallingly reductive, and a key step on the path to extremism. When the other side is evil, everything your side does is inherently good. As the Fandom Menace spreads, it contributes to the mainstreaming of misogyny, racism, and authoritarian sentiment. Farming hatred has been monetarily lucrative for community influencers, but their bottom line is having real-world consequences. By veiling their hatred with the veneer of edgy film criticism, these groups normalize hatred. This movement was never about hating a film. It is extremism using film criticism as a proxy. Disliking and criticizing a film is fine and normal. Peddling harassment, conspiracy, and misogyny? Those are radicalizing, and a step down a long, dangerous path.

The French Legislation Targeting “Religious Fundamentalism” That Has Sparked Backlash

By CTEC Research Fellow Julie Huynh

On February 17, the French National Assembly passed a bill 347 to 151 that lawmakers claimed was meant to curb the dangers of Islamism throughout France. Just this week, in April, the Senate passed the legislation with even stricter provisions than the National Assembly version, meaning that the bill now goes into discussion between the two houses. Though it is supposedly aimed at stemming extremism, it has been dubbed as the anti-Muslim bill and has sparked significant condemnation. Many Parisians spent their Valentine’s Day near the Eiffel Tower peacefully protesting, arguing that it unfairly targets a minority that already faces discrmination and violence. The bill has also faced criticism from Ambassador Sam Brownback, the U.S. ambassador at large for international religious freedom, who said, in reference to the bill, “When you get heavy-handed, the situation can get worse.” The French government’s tone towards Islam have also previously been met with criticism in late 2020 from major leaders in Turkey, Pakistan, Kuwait, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. Many more countries in the Middle East and North Africa have decided to boycott French goods.

Back in December 2020, Prime Minster Jean Castex stressed that bill is not targeting Islam, that on this contrary, “it is a law of freedom, it is a law of protection, it is a law of emancipation against religious fundamentalism.” The legislation indeed does not include any form of the word “Islam” or “Muslim”, however, the intent of the bill’s existence is clear from previous French government action and rhetoric. For example, in an interview with major French newspaper Le Monde, Castex stated, “The enemy of the Republic is an ideology that calls itself radical Islamism, whose objective is to divide French people from one another.” This bill comes on the heels of a year that has seen multiple attacks in France connected to radical Islamism, including a beheading of a history teacher. 2020 resultingly witnessed a sharp increase in anti-Muslim sentiment in France culminating in President Macron’s public vows to crack down on Islamist extremism.

The bill will fine or jail doctors who perform virginity tests and offer so-called “virginity certificates” for traditional religious marriages, make hate speech a punishable offense with up to 3 years in prison and a fine of 45,000 Euros, refuse residence permits for immigrants practicing polygamy, require all children over the age of three to be in school instead of being home-schooled to crack down on fundamentalist teaching, prohibit religious symbols like the hijab from being worn in all private-sector jobs (it has already been banned in public sector jobs and schools), impose strict controls over the funding of Islamic institutes and associations, and require these places to declare their allegiance to the “values of the republic” with the everlooming threat of being shut down if they do not do so.

This effort in France to protect the country against what the government perceives as religious extremism is part of a wider, largely right wing-driven effort across European countries. Though France was the first country in Europe to ban full-face coverings in public in 2011 targeting women in burqas, it has not been the only one. Currently in Switzerland, a referendum targeting burqas was set for vote on March 7. Similarly, other countries in Europe have followed suit in introducing burqa bans, including Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Latvia, the Netherlands, and Norway, citing reasons of public safety. These facial covering bans, however, have been turned upside down in the era of COVID where wearing facial coverings have become the norm. "What's the difference when you cover your face for religious reasons or when you cover your face for health reasons?" said Moana Genevey, a gender policy officer at Equinet. "If the burqa ban is only justified on religious grounds, it is a discriminatory law.” Dr Sanja Bilic, an operations and policy manager at the European Forum of Muslim Women, points out that these bans "criminalize a piece of clothing and no other piece of clothing is criminalized in Europe. This is problematic and it leads to Islamophobia, a gendered Islamophobia because it only targets Muslim women."

This increasing display of intolerance towards Islam in France became a hot topic again in late September 2020 when ruling party member Anne-Christine Lang walked out of a National Assembly meeting due to the presence of 21-year-old Maryam Pougetoux. Pougetoux was representing her students’ union and wore a hijab, and was speaking about how to minimize the effects of COVID on young people.

In addition, President Macron and the ruling party in France have been fending off a growing political threat from France’s far-right populist party, National Rally. The party’s leader, Marine Le Pen, espouses hardline, far-right views on race, internationalism, and economics, and has routinely targeted the French government over immigration and refugee policies. Macron’s efforts to pass this legislation are, in part, an attempt to head off the resurgent French far-right in anticipation of upcoming elections.

While France appears posed to make the bill into law in the coming weeks, such sweeping legislation that rewrites extensive portions of civil liberty law will undoubtedly spark more backlash from domestic and international audiences. It remains to be seen how France will navigate this issue in the face of pressure from allies.

The Rise and Fall of Doomer Culture

By Ben Mueller, MA Candidate in Nonproliferation and Terrorism Studies at MIIS

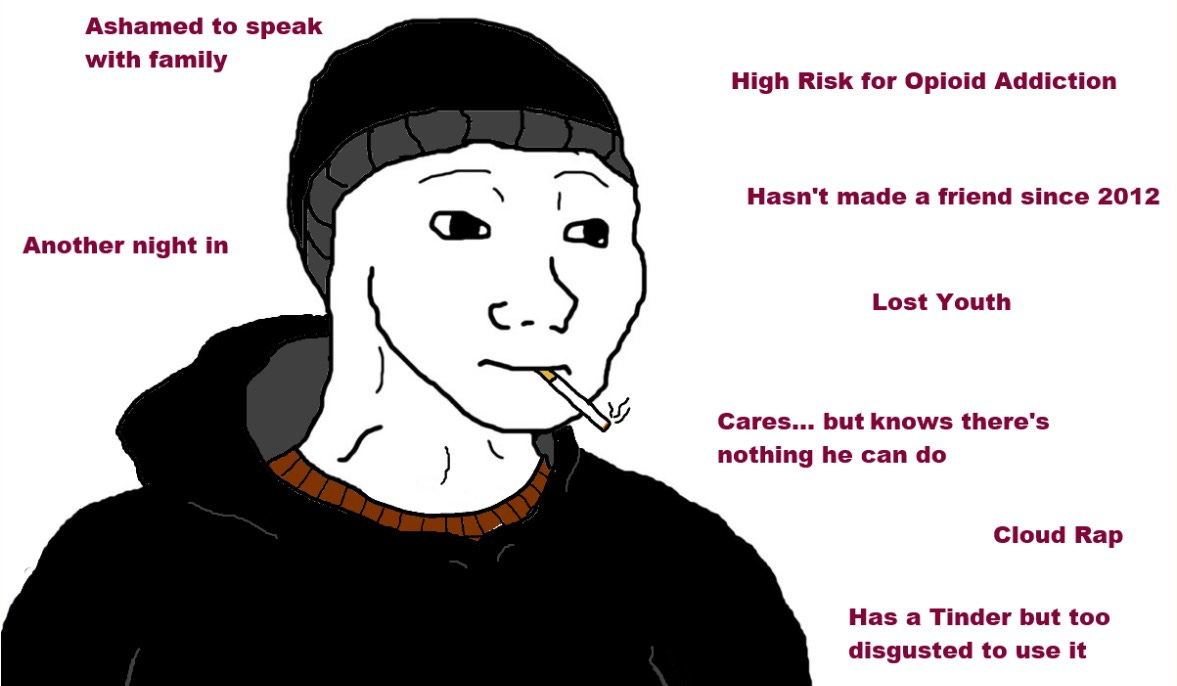

Core to the idea of the American Dream is unbridled, limitless optimism—but some communities have lost faith in the concept. Adopting the “Doomer” moniker, a new generation of extremists is rising in explicit opposition to that optimistically envisioned future. Fearing the headwinds of climate disaster and environmental destruction, they often descend into despair. Although influenced by nihilism, Doomers are primarily defined by an apathy towards the future and a feeling that the “best days are past”—in other words, that the future increasingly grim.

While many escape this spiral of cynicism, the instances of those who don’t are increasingly alarming. Recent mass shootings, most notably the terrorist attacks in Christchurch and El Paso, have had undertones of Eco-Fascism, with viewpoints that wouldn’t look out of place on fringe Doomer internet message boards.

This generation of extremist action is fundamentally different from those which came previously. Historically, so-called “eco-terrorist” groups like Earth First! and Earth Liberation Front have focused on economic terrorism, which has cost some companies millions of dollars and sparked ire among law enforcement and industry. However, human casualties have been notably absent. New groups, on the other hand, are increasingly adopting rhetoric that calls for targeting people. Some, like the Green Brigade, promote ecologically minded Nazi accelerationism on message boards; others, like Individuals Tending Towards Savagery (ITS) have already utilized murder and car bombs.

Though they cloak themselves in the imagery of left-wing anarchist groups (while recruiting from many of the same anxieties), in practice ITS also draws inspiration from and republishes extremists idolized in far-right accelerationist circles, including Ted Kaczynski. Less concerned with ideological consistency than calls to violent action, these groups integrate militaristic nihilism and pessimism into their anarcho-libertarian messaging. Their ultimate goal? To accelerate the collapse of human civilization.

With some drawn to progressive activist groups like Extinction Rebellion, others choose darker alternatives to action. Often more Malthusian than Millenarian, those attracted by the “scientific” racism of environmental collapse justifying “population control” work towards an extreme form of ethnonationalism called eco-fascism. “I only support the police if they do what I like”, quipped one image board user.

The ideal state for many Doomers seems one of post-apocalyptic freedom, where those individuals, organizations, and governments responsible for the perceived exploitation leading to society’s doom are punished harshly, and where decentralized technology like cryptocurrencies and distributed computer networks could help maintain movement cohesion after the collapse. Held up as a utopian dream of sorts, eco-fascism is seen as an alternative political and social system that would allow the groups responsible for runaway environmental destruction to be punished. Long-debunked authoritarian movements in decline are being reinvigorated by incorporating climate disaster as a staple of recruiting efforts. Since most Doomers are young, an environmentally conscious frame may shape them to be more accepting of extremist policies and beliefs. When combined with other belief systems, some of the apathy and despair can be overcome in favor of action, potentially violent in nature.

As a whole, Doomers can be defined as a new syncretic cultural movement of mostly apolitical, white, technology-savvy pessimists. They believe global challenges like Climate Change are beyond fixable, and they know who to blame with an incredible animosity towards older generations. Doomerism is less a unique movement than a common thread of despair for the future accelerating groups and individuals toward extreme action not as a remedy, but as a means of punishing those seen as squandering the earth’s resources at the expense of future generations while they’re still alive.

This common thread of despair and dystopia has itself become a cultural touchstone in popular media. Cold War films often have similar themes, but they have a resolution to the madness: nuclear conflict can be postponed, perhaps indefinitely. Eventually, things get better.

One primary source refuting any potential optimism is a 2019 essay in The New Yorker titled “What if We Stopped Pretending”. Though lambasted by the scientific and political community for its flaws, it struck a chord among Doomers. Correct or not, what matters most for the development of this movement is the perception of sufficient action. In the essay, Franzen accurately reinforces fears of climate disaster, telling a convincing narrative of our worst impulses leading to disaster.

“Accurately” because there is a thread of truth here. Climate goals have been set, missed, and pushed back for decades. An entire generation has perceived only failure after failure by policy leaders. Some have begun to take note. In the bookThe Future We Choose, written by some of the architects of the Paris Agreement, grief for the future driving pessimism and inaction is identified as one of the greatest challenges to solving the climate crisis.

Nuanced takes – like those by The Breakthrough Institute’s Zeke Hausfather arguing even these imperfect policies helped avoid truly worst-case scenarios – are probably more accurate. But failing to live up to optimistic goals year after year, opting for action that is barely adequate even to scientists has a cost.

Assumed only to be economic, a budgetary discrepancy to be balanced by future technologies and by generations of the future, this inaction could become a double-edged sword. As long as this perception of failure exists, it will continue to metastasize, to be reinforced for as long as we fail to achieve the best of outcomes. It will continue to accelerate the rise and rise of Doomer mentality.

Every milestone passed, every decade hotter than the last, every failure to properly address environmental destruction and climate change as an existential threat will only further verify this dangerous narrative. Perception will matter more than facts; even a zero-carbon society overnight would take decades (if not centuries) to have an observable effect on global temperatures.

Even so, actions can be taken to stem the tide of these perceptions. Helplessness only confirms fears of inevitable failure. We need to allow everyone across society the chance to work directly on solving environmental issues over symbolic “feel-good” solutions like banning plastic straws. Similarly, massive mobilization of resources across the world to protect the environment and climate may assuage concerns over previously failed responses.

If we don’t change the narrative of inevitable climate disaster, Doomerism will continue to accelerate radicalization and violence across the political spectrum. Worse, as we fail to address actual climate disaster, Eco-Fascism becomes only more compelling. The next generation is watching closely as our failures reshape the Overton Window – potentially to a disastrous end.