CTEC Newsletter 4: June/July 2021

Introduction

By Alex Newhouse

Hello everyone, and happy Friday! We are excited that the CTEC Newsletter is back from a short hiatus, and at the helm is CTEC’s new research lead, Erica Barbarossa. Erica recently graduated from the Dual Degree Program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies and Moscow State Institute of International Relations, and she’s an expert in online extremism with a particular focus on Russia and the Slavic region.

In this edition of the newsletter, Erica has compiled an excellent set of articles and explainers that cover some of the most important issues in extremism in terrorism. First up, our own Enrique Nusi goes in depth exploring how youth are brought into the fold by extremist movements. Next, Erica herself explores the various geopolitical and counterextremism dimensions of the United States’ withdrawal from Afghanistan. We end with the terrific one-two punch of CTEC Graduate Research Assistants Sean Kitson and Myles Flores; Sean investigates the recent resurrection of Rhodesia in the popular consciousness of far-right extremists, while Myles discusses his own experience with the history of white supremacy in the United States, and how that history informs modern-day right-wing extremism.

As always, we hope you enjoy the newsletter!

The Machinery of Youth Extremist Indoctrination

By CTEC Digital Researcher Enrique Nusi

Extremism thrives in the Internet era. It grows by exploiting anxieties over demographic changes, slowing birth rates, and demands for rapid social change in a time when COVID-19 has led to widespread economic slowdown. It does not take a propaganda department to tap into these fears: An individual acting in bad faith can share an article on a K-shaped recovery or collapsing birth rates on the right social media platform and spread an otherwise factual message with supplementary comments that primes the reader to interpret the facts through an extremist lens. It is when such actors target deep-rooted anxiety that people latch onto this messaging. When combined with external factors such as isolation and mental illness, this creates a breeding ground for people, especially youth, to become desensitized to the authoritarian outcomes which extremist ideologues desire and to resort to terrorism offline to accomplish those aims under the guise of resolving their personal demons.

Machinery of Recruitment

Research from Maxime Berube et al. shows that there is no single way in or out of extremist groups, but that entry patterns generally share influential drivers like the need for identity and belonging, power, and invincibility.1 The need for social belonging is especially important in adolescents, whose general outcomes are often tied to their perceived social standing.2

Figure 1

A person experiences isolation when they have a low tolerance for other communities or beliefs.3 Where a youth feels isolated from their main peer group, the Internet will play an increasingly important role in social interaction. This may take the form of new or deepening religious practice, isolation from family, or new risk-taking behavior like drug use and risky sexual behavior4 for which the at-risk youth will use the Internet to engage and express out-of-sight from parents or peers. The likelihood increases over time that a youth will gravitate towards fora where discussions happen around alternative philosophies, niche hobbies, and sexual or drug exploration. Many casual forums may keep discussion on-topic (where content moderation is strongest), but an isolated person may seek community spaces where the discussion becomes less regulated.

Figure 2 - Normalization of language that downplays the sexual assault of a minor while exploiting sexual insecurity to introduce the concept of the “Chad” archetype

Forums like 4chan moderate very little. It is in these spaces, where niche interests lead to long-sought social interaction, where innocuous questions can generate simple answers that ignore key facts for the sake of making the wider community feel good. “Why do women reject me?” may return answers which imply that all women are overly selective, or which impose “Chad/virgin”5 imagery or language upon the context. This seeks to deprecate a questioner, victim, or situation and introduce ideology which promotes violent misogyny and the idolization of mass murderers like Elliot Rodger. Should the inductee reject these notions, they may face severe verbal backlash, including accusations of being an FBI operative or a cuckold, placing greater pressure on the newcomer to accept the group’s view.6 By softening attitudes towards views which would be chastised in mainstream society, a meta-discourse emerges in which harmful messaging can be hand-waved away, justifying it by saying “it’s just a joke,” further priming newcomers to receive passive indoctrination from this source.7

Effectiveness and Outcomes

Extremists offer digestible explanations for all the perceived ills of society. While fact-based arguments require a degree of specialized knowledge to produce and consume, extremist arguments only need to strike a nerve.8 9 With a mind primed to receive programming from a steady stream of memetic imagery and meta-ironic humor, it becomes much easier to convince someone of their correctness by having the loudest voice as opposed to having the most reasoned argument.10

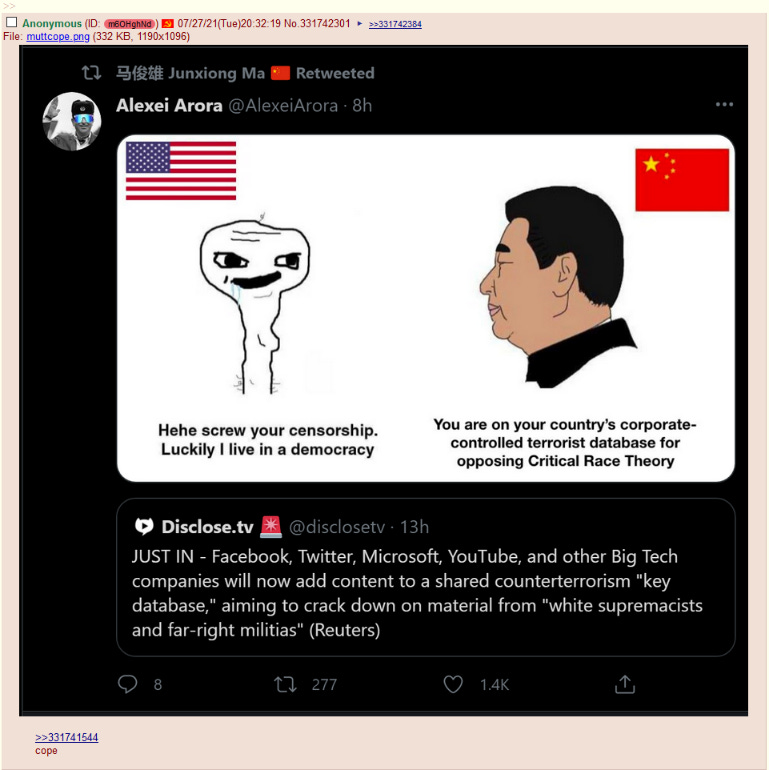

Figure 3: Meme designed to trigger support for authoritarian policy preferences by targeting extant paranoia in extremist spaces

Even though traffic to 4chan is a quarter of what it was in May 2018,11 this effective technique is still very visible off-platform. 4chan and others are incubators for memes that trivialize hate and violence, and those memes tend to flow into the mainstream from these arcane sources furthering the reach of potentially radicalizing material to people who may have otherwise avoided these spaces.12 While social media companies have taken steps to limit hate speech on their platforms, several cracks remain that allow it to proliferate, while the biggest actors actively resist government efforts to hold platform owners to account.13 This has enabled so-called “memetic warfare” to evolve into its current form as an effective tool for rallying the disaffected and vulnerable to their cause.

While effectiveness can only broadly be measured in terms of how far a message can reach, the outcomes of youth recruitment to extremist causes are obvious and occurring with increasing frequency – Philip Manshaus,14 Patrick Crusius,15 Brenton Tarrant,16 and Kyle Rittenhouse17 all had significant exposure to extremist content incubators,18 19 and all had stated explicit motivation for committing acts of violence that aligned with their content consumption.

Dr. Jeffrey Bale of the Middlebury Institute of International Affairs defines terrorism as “the use of violence, directed against victims selected for their symbolic or representative value, as a means of instilling anxiety in, transmitting one or more messages to, and thereby manipulating the perceptions and behavior of, a wider target audience”.20 With this definition in mind, the outcomes of violence resulting from repeated exposure to extremist content take on a new dimension. While there is likely not a singular source directing messaging on these content incubators, many of the policy preferences espoused by perpetrators of violence align with governments and groups that profess authoritarian, nationalist leanings, giving little incentive for such actors to solve the problem of Internet-induced violence.

Thus, the violence that arises from these corners mirrors Bale’s definition of terrorism: Elliot Rodger, perpetrator of the Isla Vista sorority shooting, targeted women as the source of all evil. Before this attack, he released a manifesto detailing his personal suffering at the hands of this perceived evil, and he intended for the world to read it and accept his view that women and the systems that enable them are the ultimate evil.21 Brenton Tarrant, perpetrator of the Christchurch shootings, targeted Muslims whom he believed to be part of a conspiracy to replace white European populations, and released a manifesto to promote the idea of white genocide to others who might not have been receptive without the spectacle of tragedy to pique their curiosity.22 This fed into the El Paso Walmart shooting in 2019 and the attempted shooting at the Al-Noor Islamic Center in Oslo, Norway the same year.

Repeated exposure, normalization, and idolization of these actors has created an environment in which disaffected youth see terrorism as a thing to be praised and the perpetrators as actors to be lionized and emulated. Should the authorities come investigating, it can all be dismissed as a collection of jokes spread by irreverent anons who are just doing it for the lulz.

No Easy Answer

A solution to this may seem simple: why not just shut down the “internet hate machine,” as it has been termed? Beyond the logistical difficulties of pursuing sites that can jump with ease to new servers in jurisdictions that may benefit from such content, the ethical concerns of limiting free expression and speech are too great to seriously consider a blanket ban of all such services, especially where they may be used to circumvent genuine suppression of dissent in jurisdictions like Hong Kong or Taiwan.23

Yvon Dandurand of The Global Initiative Network has suggested a robust regime of social inclusion programs which target at-risk youth based on the risk factors mentioned at the beginning of this article. While her paper acknowledges the need for further research into the social-psychological factors that play into extremist recruitment in online spaces, her solution identifies extant gang prevention programs as models for potential counter-radicalization programs.24 Jessica Darden of the School of International Service at American University takes a similar tack, though she identifies further information needs like program durability on youth attitudes. Darden also adds an additional focus on the recruitment of women into extremist organizations, for example into Boko Haram, and the importance of family in countering radicalization narratives.25

Given that a punitive approach would encroach on the rights of everybody on such platforms, it would be poor policy to issue blanket bans on such content. An in-depth quantitative analysis of social media policy by Jithesh Arayankalam and Satish Krishnan of the Indian Institute of Management Kozhikode suggested that the more governments try to moderate social media spaces, the more people may resist such efforts and engage in social media-induced offline violence anyways.26 Thus, solutions which resemble those of Dandurand and Darden may offer more lasting results. By helping youths improve resilience against such messaging through stronger friend and family bonds, it may be possible to prevent the issues that cause them to seek out these places early on.

There are many more issues to resolve. Just because such programs may exist in educational or community spaces, there is no way to guarantee that a parent won’t radicalize their own children. The case of Jacob Anthony Angeli Chansley, known by the moniker QAnon Shaman, involves several factors not deeply explored in mainstream research on countering youth extremist recruitment, exemplified by Chansley’s mother’s vocal support of his actions in the January 6th US Capitol Building insurrection.27 The role played by mental health conditions too is often overlooked in favor of the broadest possible explanations.

While deeper involvement in family and real-life social groups may help slow the spread of ideologies associated with real-world violence, the perpetrators of the worst social media-induced violence often suffer from more than social isolation, though it may be a key trigger for entering these spaces in the first place. While effort should be made to include the most ostracized in community activities to get them invested in their surroundings, identifying which permutations of isolation and mental health status most strongly correlate with offline violence must be a top priority in countering the recruitment of youth to extremist causes.

The United States’ Withdrawal from Afghanistan and The Rise of the Taliban: How This Affects Russia and the Future of US-Russian Relations

By CTEC Research Lead Erica Barbarossa

For decades, the United States and Russia have served as political opponents on the world stage. With events such as the annexation of Crimea and Russian disinformation campaigns targeting the U.S. 2016 presidential elections, US-Russia relations arguably stand at their worst since the Cold War. One major issue that stands between the two countries has been the ongoing situation in Syria. Now, with President Biden pulling the US military out of Afghanistan after 20 years of engagement, the possible destabilization of Afghanistan and the rise of the Taliban could stand to be the next big political battleground between the opposing countries.

As of now, about 90% of the United States and NATO’s withdrawal is complete, only leaving about 600 troops to guard the embassies. Since their swift exit, the Taliban has surged to fill the void and take control of various areas of Afghanistan. Thousands of families have been displaced as the Taliban seizes provincial capitals and advantageous cities. Strategic trade routes have also been targeted, namely major routes and exit points bordering Iran, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. In its efforts to seize territory, the Taliban was initially met with tough resistance by the government and the inhabitants, which has since waned. Now, most city officials surrender or accept bribes to abandon their home. By all accounts, the United States government predicts that if things continue this way, Afghanistan could fall within six to twelve months. Yet despite this harrowing prediction, President Biden remains firm on his decision to pull out troops.

So what is the Russian perception of this growing crisis? Based on recent publications in Pravda.ru, one of the most well-known Russian websites, the situation in Afghanistan has brought on concerns of destabilization of the Central Asian region, a growing threat of terrorism and extremism, and a flurry of conspiratorial narratives concerning possible ulterior motives behind the United States’ sudden departure.

Russia, which fought a ten-year war in Afghanistan in the 1980s, has of late been a diplomatic mediator for the country. Clashing with the United States for influence there, Russia has hosted numerous talks with the different Afghan factions, including the Taliban. Despite this recent diplomatic relationship, the Taliban is prohibited by the Russian government to this day. In 2003, the Taliban was officially designated as a foreign terrorist organization by the Russian Federation after the Taliban backed Chechnya’s bid for independence and tried to sell weapons to Chechen rebels. It is unlikely that the Kremlin will change this designation anytime soon, but its overtures to Taliban officials increase the geopolitical complexity in the region.

With the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Russian government appears to be paying significant attention to the increasing danger of extremism and terrorism that could affect it and its Central Asian allies. As of now, Tajikistan stands as the main concern for this growing threat. So far, thousands of Afghan troops and displaced families have retreated to the country after Pakistan made the decision to turn down refugees. With this development comes a heightened possibility of terrorists entering Russian territory from Tajikistan (via Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan) to spread their ideology or attack Russian civilians. Due to the continuing presence of terrorist networks among Afghan communities, there is a risk that some may follow the playbook from the Syrian refugee crisis and use refugee communities to disguise threatening activities.

In addition to this, a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan could draw Russia into military conflict if the Taliban chooses to attack its CSTO allies. The CSTO (Collective Security Treaty Organization) acts much as NATO does and is an agreement between Russia and most of the Central Asian countries. Therefore, like NATO, if a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan were to attack any of the CSTO countries in Central Asia, Russia would have no choice but to militarily intervene. Recently, the Taliban has made assurances to Russia that it will not allow anyone in Afghanistan to attack Russia or its allies, however only time will tell if this promise holds.

Beyond the threat of terrorism, the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan also has the chance to threaten Russia’s influence in Central Asia. Reports in Pravda.ru insinuate that the United States left Afghanistan so that the US could move more soldiers to Central Asian countries to challenge Russia’s leadership in this geopolitical region. A greater US presence in Central Asia has aggravated US-Russian relations before, and in this case, Russia has directly warned President Biden against it. Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister, Sergei Ryabkov, called this possibility absolutely “unacceptable” and promised that if done, it would negatively affect US-Russian relations.

Beyond these supposed Central Asian ulterior motives, publications in Pravda accused the United States of swiftly leaving Afghanistan so that they could offer the leftover weapons and military equipment behind for the Taliban or other rebel groups. The reasoning given for this is that an armed Taliban or rebel group would better threaten Russia’s security. In an interview found on Pravda.ru with Alexander Perendzhiev, an associate professor of the Department of Political Science and Sociology at Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, when asked about the military weapons and equipment left behind, he says it was done on purpose and that, “The situation looks like it was just preparing bandit formations, so to speak, of a professional sense in order to now blow up Central Asia.”

Distrust between the United States and Russia concerning the Taliban appears to be a common theme, as witnessed by the recent New York Times article, which claimed that Russia offered Taliban militants bounties to kill US soldiers. It seems that, as the situation in Afghanistan escalates, the potential for friction and distrust between the United States and Russia only grows along with it.

Rhodesia's Online Revival

By CTEC Graduate Research Assistant Sean Kitson

Before Zimbabwe, there was Rhodesia. This unrecognized state located in southern Africa was once a British colony, which bordered Zambia, Botswana, South Africa, and Mozambique. A relic from the European colonial race for Africa of the 1800s, Rhodesia was an oppressive, racist, apartheid, minority white-controlled society with a population of approximately 7 million people. After WWII, the British government refused to grant Rhodesia independence until it enacted majority rule within the country's government.

This led to the civil conflict known as The Rhodesian Bush War, which lasted from 1964 to 1979. This was a three-sided conflict, where the Rhodesian Security forces were fighting the Zimbabwe African People Union (ZAPU) and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). These left-leaning guerilla groups ran insurgent campaigns against the Rhodesian government, while also battling one another.

Rhodesia maintained a system of apartheid during its existence. A system of social, economic, and political discrimination was present within the very foundation of the unrecognized state. The minority white population of the country maintained a complete monopoly on power in the country's politics and economic spheres. In 1980, after a lengthy insurgency, the white-run government acceded to majority rule and the country was renamed Zimbabwe.

However, Rhodesia has not remained as a simple historical footnote, a relic of a post-colonial Africa. Famously, Dylann Roof, the perpetrator of the racially motivated shooting in Charleston, North Carolina, which targeted Black churchgoers, published his manifesto on a website titled “The Last Rhodesian” and had been pictured wearing a pin of the Rhodesian flag on his jacket.

Extremists have also incorporated Rhodesian nostalgia with the aesthetics of reaction that have been popularized among far-right accelerationist communities. Members of Patriot Wave, one of the first named groups to emerge from the Boogaloo Movement, frequently promoted Rhodesian apartheid and anti-Black violence in its chat rooms.

Today, radicalized young white men online have found in Rhodesia a nation to praise and romanticize. The resurgence of Rhodesian propaganda has found a niche white supremacist community across social media platforms. On Instagram, Facebook, and most recently TikTok, one can find individuals saying in a “joking” manner that “there is no time to party, we have to take back Rhodesia.” This commentary is often followed by footage of the Rhodesian Bush War, with the song “Rhodesians Never Die” over the footage, which has become the unofficial anthem of this online movement.

Much of the video edits are footage of Rhodesian soldiers posing in the bush, fighting insurgents, jumping out of helicopters, and simply just posing with their squadron. These soldiers are often wearing unique military kits, consisting of short shorts, tennis shoes, safari hats and armed with Belgian FN FALs. These aspects have all come to be part of the lost Rhodesian aesthetic that white supremacists celebrate.

Descriptions and hashtags of these videos often contain a variety of memetic and coded language. Phrases such as “Make Zimbabwe Rhodesia Again,” or “Let’s Slot Some Floppies” (“slot” meaning kill and “floppies” referencing the insurgents they fought) are often weaponized as veiled racial epithets towards Black people in general. Nuanced and masked language such as this is an essential part of the online community. New terminology continues to be created and used as a way to discuss and promote this white supremacist movement. Silly-sounding and seemingly innocent phrases are used as a means to disguise the racist and hateful undertones of the narrative.

Historical Rhodesian merchandise has seen increased sales since Dylann Roof’s use of the Rhodesian flag. Vintage propaganda and equipment are sold as historical memorabilia in the form of posters, flags, and stickers, t-shirts, and more. Ranging from historical slogans used during the war to patches with “Make Zimbabwe Rhodesia Again” in the pattern of former President Trump’s campaign slogan.

Some Rhodesian fanboys try to deny the racist past of Rhodesia and argue that the white minority practiced a sort of “progressive apartheid.” The other individuals who follow, edit, and enjoy these Rhodesian memes do not engage in historical revisionism; rather, the racist apartheid minority white-rule is the reason they celebrate Rhodesia in the first place.

White supremacists attribute the fall of Rhodesia to conspiratorial narratives of Jewish-controlled European nations refusing to intervene, and vilify the African political movements attempting to gain self-determination, as nothing more than communist puppets from China and the USSR. These believers also subscribe to the belief that the West betrayed and turned its back on this white paradise.

This Rhodesian rhetoric often operates as a narrative adjacent to conspiracy theories like white genocide or the Great Replacement, since the insurgents targeted white villagers and farmers during the war. This factor is often used to play on the fear of Black on white violence and is used as justification of ethnonationalist oppression and race-based segregation.

Rhodesia is painted as a martyred state for white supremacists online, a state where one can reminisce about its segregation and apartheid policies. The online revitalization and historical revisionism surrounding the history of the country is a dangerous and radicalizing phenomenon. As pro-Rhodesia social media accounts continue to proliferate online, the spread of dangerous disinformation and violent racist rhetoric increases. It is crucial to combat this spread of false information and to recognize masked white supremacist movements that attempt to infiltrate mainstream conversation through the guise of memes, gun culture, military history, or historical memorabilia.

A Brief History of America's White Supremacy: Where It Started and Where We Are Today

By Graduate Research Assistant Myles Flores

As a Black man in the United States, I have always been perplexed by white supremacy. Throughout my life, I have experienced overt instances of racist remarks directed towards me, along with several acts of poor treatment due to the different color of my skin. Despite this, I have been respectful to everyone regardless of skin color and given no excuse to be treated subpar in society. 7 in 10 Black people, irrespective of their upbringings, have similar stories to mine, experiencing some kind of adverse treatment because of the color of their skin. This negative treatment is encouraged by white supremacy as most of this mistreatment involves a person believing—consciously or subconsciously—that they are superior to Black people.

The question, ‘what are the drivers of white supremacy?’ plagues not only my mind, but also the minds of the best extremism experts in the world and everyday people alike. Perhaps it’s the white supremacist's upbringing or culture? Or psychological issues? Or a general hatred of anyone who doesn’t look like they do? Whatever the answer is, white supremacy exists today and upholds an idea of hatred against millions of people.

We can trace white supremacy as far back as the 18th and early 19th centuries during the dawn of the United States. One of the fathers of this toxic ideology is John H. Van Evrie, who paraded anti-Black sentiments and regarded Black people as subhuman—but essential for doing the “white man’s work.” This act of believing in white superiority was also held tightly by even the founding fathers. Both Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin upheld racist white supremacist ideas, with Franklin even stating that he would have preferred Africans to never have existed in the colonies. And of course, infamously, Jefferson utilized slave labor until his death, refusing to free them and even raping one of his slaves, fathering the children and enslaving them as well. Moreover, the white supremacist ideology transcended to even those that fought against slavery. An example of this is Samuel Sewall, an infamous ringleader of the Salem Witch trials and a writer of the first anti-slavery pamphlet. However, Sewall still upheld racist ideas towards Black people, regarding them as people with “a kind of extravasate Blood,” often referring to Black people as aliens. By presenting these ideas, the founding fathers, Sewall, and Evrie show that white superiority existed in all aspects of early American society. These men, along with thousands of other complicit people, helped to plant the seeds that would blossom into systematized white supremacy and plague American institutions, government, and society for two centuries.

Today hundreds of groups thrive off ideologies paraded by the founding fathers, Evrie, Sewall, and millions of others throughout history. Each and every one of the groups and adherents to the groups has their motives and drivers for joining a group. In an article of a white man talking about why he joined a white power skinheads organization, he shares his disgust towards Black people, which originated from his mother’s Black boyfriend mistreating her. But how and why does this hate for one Black person transcend to Black people as a whole?

Perhaps the questions I pose in this newsletter are beyond our scope of understanding. white supremacy has been driven by the fact that minorities are increasingly finding a place in all aspects of society. This drastic change and increase of minorities in society have led white people to embrace white supremacist conspiracy theories, political action, and politicians. Furthermore, prominent figures such as former President Trump have helped further the white supremacist narratives in the United States. During Trump’s presidency, white supremacy and disguised white nationalism surged because of his appeal to white victimhood.

Today white supremacist groups feel more empowered than ever after Trump’s complicity in upholding and refusing to condemn their ideas. In the last 2 years, white supremacist groups have grown by 55%. Groups such as the Klu Klux Klan (1865), Knights of the White Camellia (1867), White League (1874), and the Red Shirts (1875), are all examples of long-lasting white supremacist group that have a tainted legacy that is upheld today. While some of these groups are now long gone, they have played a role in creating a legacy that supports white supremacy and white victimhood.

In recent days, more people are drifting towards white supremacy and unknowingly contribute to a horrible problem in society. Whether it’s refusing to acknowledge America’s racist past or mistreating a Black person, we all have our work cut out for us. We must now figure out how to shift away from this dark moment in U.S. history, diminishing the hate amongst fellow Americans. I mean, at the end of the day, we’re all humans, right?

Berube, M., Scrivens, R., Gaudette, T., & Venkatesh, V. (2019). Converging patterns in pathways in and out of violent extremism: insights from former Canadian right-wing extremists. Perspectives on Terrorism, 13(6), 73-89

Newman, B. M., Lohman, B. J., & Newman, P. R. (2007). Peer group membership and a sense of belonging: their relationship to adolescent behavior problems. Adolescense, 42(166), 241-263.

Cole, J., Alison, E., Cole, B., & Alison, L. (2010). Guidance for identifying people vulnerable to recruitment into violent extremism. Liverpool: University of Liverpool.

Ibid, pp. 7-9

A meme which often depicts a crudely drawn “virgin” figure in a humiliating situation followed by a cartoonishly masculine or cleanly drawn “Chad” figure in a situation where he has money, power, female companionship etc. that the “virgin” cannot achieve.

Bale, J. M. (2017). The darkest side of politics, I. New York City: Routledge. pp. 25-26

Billig, M. (2001). Humor and hatred: the racist jokes of the Ku Klux Klan. Discourse & Society, 267-289.

Ahmadi, B. (2015). Afghan youth and extremists: Why are extremists’ narratives so appealing? United States Institute of Peace Peacebrief, 188, 3-4.

Baele, S. J., Brace, L., & Coan, T. G. (2021). Variations on a theme? Comparing 4chan, 8kun, and other chans' far-right "/pol" boards. Perspectives on Terrorism, 65-80.

Hagman, L. (2012). Conflict talk in online communities: a comparative study of the Something Awful and 4chan web-forums. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 49, 51-54.

Trackalytics. (2021, July). 4chan.org. Retrieved from https://www.trackalytics.com/website/4chan.org/

Phillips, W. (2019). It wasn't just the trolls: early internet culture, "fun," and the fires of exclusionary laughter. Social Media + Society, 1-4.

Reuters. (2021, July 27). Google takes legal action over Germany's expanded hate-speech law. Reuters.

Age 21 at the time he attempted a mass shooting on the Al-Noor Islamic Center in Oslo, Norway.

Age 21 at the time he committed capital murder at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas.

Age 28 at the time he carried out a terrorist attack on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Age 17 at the time he shot and killed 2 people during the Kenosha Black Lives Matter protests – a trial is still pending at the time of publication

Ekman, M. (2020). Social media racism: affective circulation and cultures of fear. Global Discourse, 1-3.

Groves, S., & Bauer, S. (2020, August 27). 17-year-old arrested after 2 killed during unrest in Kenosha. Associated Press.

Bale, J. M. (2017), 4

Rodger, E. (2014). My Twisted World. Isla Vista. 133, 135-137

Tarrant, B. (2019). The Great Replacement. Christchurch.

Doffman, Z. (2019, August 31). Shock Telegram Change Protects Hong Kong Protesters from China--But 200M Users Affected. Forbes.

Dandurand, Y. (2015). Social inclusion programmes for youth and the prevention of violent extremism. Countering Radicalisation and Violent Extremism Among Youth to Prevent Terrorism, 23-36.

Darden, J. T. (2019). Tackling terrorists’ exploitation of youth. The American Enterprise Institute. 11-14

Arayankalam, J., & Krishnan, S. (2021). Relating foreign disinformation through social media, domestic online media fractionalization, government's control over cyberspace, and social media-induced offline violence: insights from the agenda-building theoretical perspective. Technologica Forecasting & Social Change, 7.

Graziosi, G. (2021, March 4). Mother of 'QAnon Shaman' Jacob Chansley defends her son and repeats election conspiracy theories. Independent.