CTEC Newsletter 5: August/September 2021

Local Partners and Counterinsurgency, Non-Fungible Tokens, and Far-Right Conspiracy Theories

Introduction

By CTEC Research Lead Erica Barbarossa

Hello everyone and welcome back to the CTEC Newsletter! We have a great edition for all of you this time and are happy to announce that the newsletter will be published every two months from now on, so keep a look out and be sure to subscribe. If you are part of the Middlebury community and are interested in getting published in future CTEC Newsletters, please reach out to me at ebarbarossa@middlebury.edu.

We start out this newsletter with an explainer of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and how they may be abused by bad actors, written by MIIS Nonproliferation and Terrorism Studies (NPTS) alum Allison Owen. Next, Myles Flores and I each explore different dangerous right-wing conspiracy theories that are proliferating online today.

To complete this edition of the newsletter, we present an exciting new section on the Asymmetric Conflict Initiative, one of CTEC’s five areas of focus. We hope for this to be a recurring section that highlights the great work being done by Professor Orion Lewis, Chuck Woodson, and the students of Middlebury College and the Middlebury Institute. Launching this section is Emily Lieb, who expertly analyzes cooperation with local partners in counterinsurgency success.

Hope you enjoy it!

Bad Actors and Non-Fungible Tokens

By Allison Owen, MIIS NPTS Alum ‘21

What is a non-fungible token (NFT)? Think about a unique digital asset pinned to a token that comes with an identification code. Now, these assets can take many forms., from artwork to real estate and even trading cards. No matter what form it takes, the buyer can confirm whether they are purchasing the original or a replica because a record of transactions is stored on a blockchain-based immutable ledger. As such, while there might be multiple editions of an item, each NFT can (in theory) be validated.

Due to each token being unique, the value of each digital asset can increase dramatically. This year led to a massive demand surge, leading to some NFT prices skyrocketing and sparking the attention of large corporations. On August 23, Visa announced its purchase of the NFT-based digital avatar, CryptoPunk, for $150,000. Two weeks later, the auction for digital forms of several masterpieces by Russia’s Hermitage Museum came to a close, resulting in the museum making $444,500. However, it is important to note that some NFTs, such as those by the artist Beeple, have gone for millions of dollars.

Let’s look at the underlying risk involved in NFT markets. First, it is necessary to recognize that NFT marketplaces can be a primary area for fraudulent or criminal activity, as shown last March when fraudsters hacked into user accounts for the NFT marketplace, Nifty Gateway. Reportedly, victims either had NFT art stolen outright or had NFT art illicitly purchased with saved credit card information and then stolen. To combat this type of fraudulent activity, experts are turning towards the development of a registry of stolen or fraudulently purchased NFTs. If a list of these items are available for NFT marketplaces to screen, then these items could potentially be taken down prior to purchase.

Fraudulent behavior can also result in misidentification of NFTs, as shown by the sale of a fake limited-edition Banksy print on OpenSea in early March. After hacking into the artist’s website, the individual posted a link to the NFT, which sold for roughly $380,000. The hacker has since returned the money, but nonetheless, this scam shows the risk involved in NFT marketplaces. Although some marketplaces state that such behavior will not be tolerated, a system of know your customer (KYC) policies and ongoing monitoring needs to be implemented to back up this statement.

To add to the necessity of NFT marketplaces implementing KYC policies, NFTs can also be used as a general tool for money laundering. Purchasing and selling NFTs can be used as a layering method, allowing for entities associated with criminal activities to obfuscate the source of funds. For those unfamiliar with the money laundering cycle, layering is the second stage of money laundering wherein the launderer attempts to blur the origin of the illicit funds so law enforcement cannot follow the money. While there are clear advantages for money laundering through the NFT markets, criminals also face some drawbacks. For instance, if an individual were to purchase an NFT for a certain price, the intrinsic volatility of the markets mean that there is no guarantee that the criminal will be able to recoup all of its money. Nonetheless, if a bad actor wants to move money quickly, then they may take this risk. It is necessary to work with NFT marketplaces and confirm that KYC policies are in place and ongoing monitoring occurs to restrict this activity.

Given the growing popularity of NFTs, it is necessary to understand the risks involved in NFT marketplaces and take precautions against them being used by bad actors. As large players continue to focus on NFTs, these digital assets will continue to grow in value. Although most of this activity is legitimate, there are underlying risks in regard to fraudulent behavior. It is necessary to address these risks early on and work with NFT marketplaces to confirm they have the necessary resources in place.

Critical Race Theory: How a Movement on Racial Justice Became a Target of Right-Wing Conspiracy Theorists

By Myles Flores, CTEC Graduate Research Assistant and MA NPTS Candidate at MIIS

"It's racist!"

"It doesn't belong in our schools!"

“It’s anti-white propaganda!”

Over the past year, right-wing activists have used these slogans and others in attacks on critical race theory. We hear this theory thrown around a lot these days, but what exactly is critical race theory and how does it relate to right-wing extremism?

Critical race theory, or CRT, is one of the most debated topics in the United States, as the theory attempts to offer an explanation for latent and systemic racism in the United States. Moreover, the concept seeks to explain how and why racism is so deeply embedded in all aspects of American society, and how we all, knowingly or unknowingly, contribute to racist systems. The theory traces its roots back to the second half of the 20th century, when lawyers began to analyze prejudiced frameworks embedded in the American legal system. A good example of an event CRT seeks to explain is when government officials drew red lines around areas deemed as "poor financial risks" in the 1930s. More often than not, these drawn lines explicitly or implicitly targeted an area's racial demographics. As a result, banks would refuse to offer mortgages to these “people with poor financial risks,” which were, for the most part, Black people.

For most of its history, CRT has primarily been taught in graduate and law schools as an advanced sociological and legal topic. CRT rarely appeared in mass media until 2019 when the New York Times published the 1619 Project. This long-form journalistic effort marked the 400th anniversary of the first slaves in the United States and attempted to reshape the way that Americans discussed the founding of the country. The 1619 Project compiled essays, commentaries, and poems all revolving around race-based issues, much of which was based on extensions of CRT philosophy. Almost immediately, both CRT and the 1619 Project were demonized by conservatives, with former President Trump calling the theory and project "toxic."

Since then, and especially over the past year, CRT has been under attack by Republican legislators and activists from all over the country. Many of these CRT critics attempt to characterize the theory as a systematic demonization of white people and the United States itself for being oppressors, and as a glorification of Black people as hopelessly oppressed victims. This is, it should be clear, a massive oversimplification. But due to intentional efforts by influential conservative politicians and academics to misconstrue CRT, hundreds of thousands of Americans have been wrongly convinced that the theory is anti-white propaganda, thus creating a division between white and non-white people. This division between whites and non-white people, coupled with the belief that white people are being unfairly villainized, has led to the CRT being targeted by far-right movements. Right-wing extremists and conspiracy theorists alike have hijacked and weaponized CRT as proof to support outlandish racist conspiracies in the United States.

Adherents of the New World Order (NWO), the Great Replacement, and race war conspiracy theories have all varyingly co-opted CRT to justify their fringe beliefs. The NWO theory alleges that the financial elite are undertaking a worldwide plan to destroy governments, enslave humanity, and create a one-world dictatorship. The conspiracy theory has anti-Semitic roots linked to , and adherents often attack significant Jewish banking figures and believing them to be the plan's creators. The Great Replacement theory and Race War narratives are similar, as the Great Replacement theory proposes an increase in the marginalization of white people via orchestrated “invasions” of non-white immigrants. Many believers allege that the subsequent decrease in the proportion of white people in a population will eventually lead to an all-out conflict between white people and all other races, otherwise known as a race war. Comments found on far-right websites often house articles that identify CRT as a weapon to fuel Cultural Marxism, which is another theory linked to NWO paranoia and Great Replacement conspiracism.

The NWO, the Great Replacement, and race war theories may seem to be different conspiracy theories, but they all have one key element to them: Cultural Marxism. Cultural Marxism is an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory stemming from the 1930s. In essence, adherents believe that Jewish people created a form of Marxism that targets cultural systems instead of economic ones (for example, supposed cultural Marxists are alleged to be striving for the destruction of Christianity). Today, Cultural Marxism has been levied to support the narrative that Democrats are actively dismantling American society.

This mishmash of conspiracy theories and mischaracterizations of anti-racist education has created a mobilized group of misinformed people, many of whom have already shown a willingness to take on-the-ground action. Passionate opponents of CRT also contribute to delegitimization of Black-led activism efforts. Further, their tendency to target school boards and local politics has shown a worrying capacity for poisoning educational administrators and politicians against teaching children about white supremacy.

Look, I get it. Talking about race in the US is hard, and a theory that confronts racism head-on leaves many wary. However, it is important to stay informed and push back against efforts blocking CRT. These efforts made by misinformed Americans and led by conservative politicians are dangerous and help validate more threatening racist, and hateful conspiracy theories that can and are inciting violence among their followers.

Anti-Semitic Conspiracy Theories in a Pandemic World

By Erica Barbarossa, Research Lead at CTEC

According to the Anti-Defamation League, anti-Semitism continues to remain at a historic high. This startling peak of anti-Semitic sentiment can be attributed in large part to the increase of online interactions since the COVID-19 pandemic caused the world to sequester indoors. This has resulted in large numbers of people becoming newly exposed to and radicalized by dangerous anti-Semitic conspiracy theories being spread in online communities.

One of the most common anti-Semitic theories found online is the presumed nefarious involvement of Jews in the pandemic. This conspiracy theory developed on white supremacist and neo-Nazi forums, but quickly trickled down to mainstream platforms as people, frustrated by the pandemic, looked for someone to blame. Theories of this nature vary widely, but most claim that Jews created the virus for evil purposes, such as destabilizing society or controlling the masses via vaccines. Another subset of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories believe that instead of creating the virus, Jews instead fabricated the pandemic altogether. Most anti-Semitic conspiracy theories propagate the idea that Jews control powerful facets of society, such as the media, government, and education system. Using this control, Jews are able to manipulate society into believing false ideas. Adherents of Holocaust denial conspiracy theories, which has been growing in popularity, believe that Jews supposedly made up the Holocaust to victimize themselves and villainize white Europeans. Considering that Jews were apparently able to falsify a genocide, it is not a stretch for adherents to believe that an entire global pandemic could be fake as well.

Extremists also frequently blame Jews for pushing forward gun control legislation. In a tragic pattern, anti-Semitic tweets, hashtags, and memes quickly follow new mass shootings, claiming that these events are “false flags” organized by Jewish elite. These allegations feed into the conspiracy theory that Jews are staging these events in order to take away Americans’ Second Amendment rights. All of this is to ultimately make it so that Americans have no means to protect themselves or fight back when Jews supposedly try to enslave the population.

One of the most concerning trends in far-right anti-Semitism, though, is the confluence of QAnon with more explicitly anti-Semitic versions of its core narratives. QAnon was built on anti-Semitic dogwhistles and targeting influential Jewish individuals and families, but most big influencers have generally avoided explicitly targeting Jews as a whole. This has changed over the past year.

Following the deadly siege on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, almost every American has become familiar with the fanatical tales of a democratic ‘Deep State’ that engages in the sex trafficking of children and performs satanic rituals. This outlandish conspiracy theory has always held anti-Semitic undertones, as seen by the repurposing of the anti-Semitic idea that Jews murder Christian children to use their blood in rituals. Following the crackdown on Q-related content on several large social media platforms, many adherents moved over to Telegram, a messaging platform with less restriction and moderation. In this permissive environment, QAnon content has evolved into more explicit levels of anti-Semitism. This change is best characterized by GhostEzra, a QAnon influencer on Telegram who has recently been outed as 39-year-old Robert Smart from Florida. Smart has an impressive following of more than 330,000 subscribers, making him the most popular QAnon influencer on Telegram. Among his Q-related posts, Smart also posts pro-Hitler propaganda alongside many of the anti-Semitic conspiracy theories mentioned in this piece.

Based on his posts, Smart appears to be increasingly influenced by the Christian Identity Movement, a virulent anti-Semitic ideology that asserts that Jews are the literal spawn of Satan. Considering Smart’s followership and the ability QAnon has had in motivating believers towards violent action, the combination of QAnon beliefs with anti-Semitic conspiracy theories is an extremely dangerous concoction that may very well lead to a rise in attacks against Jews by Q adherents.

Conspiracy theories that target a defined group of people rarely stay only online. According to an unclassified DNI report on domestic violent extremism, the Intelligence Community believes that racially or ethnically motivated violent extremists (RMVEs) pose a very lethal threat in America this year, with RMVEs likely to conduct mass-casualty attacks against civilians. Considering this threat and the rise of anti-Semitism in the last few years, it is essential that law enforcement and the American public remain vigilant as coronavirus restrictions lift and society returns to normal.

A note from Middlebury College’s Professor Orion Lewis, introducing the Asymmetric Conflict Database project and the importance of this research:

For the last four years, CTEC has been developing a large-scale, student-driven research project focused on the global policy lessons of counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency. As the “forever wars” in Iraq and Afghanistan highlight, insurgency is an inherently difficult problem to solve in any pure military sense. Instead, the lessons of insurgency highlight the importance of the non-military and non-kinetic aspects of statecraft. How to use force effectively in a counter-insurgency and how to build up effective institutions are thus two sides of the same COIN (counterinsurgency). Working with myself and Chuck Woodson (US Army ret.), students have developed numerous projects on the lessons of Special Operations and COIN in the post-9/11 era. These range from studies on nonproliferation of WMD and military direct action against terrorists, to policies focused on building partnerships with host nations and cultural engagement. At the same time, students have recognized the importance of emerging asymmetric threats, such as Russian and Chinese disinformation campaigns. Thus, we are developing new lines of research focused on great power asymmetric conflict and the ways this competition is playing out in areas such as cybersecurity, foreign intervention, and public influence campaigns. Whether perpetrated by nonstate insurgents or state-aligned actors, the tactics of asymmetric conflict have proven valuable to a wide-range of actors. Therefore, policy lessons in this area will continue to remain of relevance, and the need for further research remains.

LOCAL PARTNERS AND COUNTERINSURGENCY

By Emily Lieb, Sophomore at Middlebury College

RESEARCH QUESTION:

How does the practice of cooperating with local partners contribute to counterinsurgency success?

For a successful mission, counterinsurgents must gather critical information on insurgent locations, identifications, and activities. To do so, they can access the public for information directly, or work with local partners1 to obtain local and cultural knowledge. Collaborating with local partners is considered essential for successful counterinsurgency.2 Local partners possess language, cultural expertise, and often leverage over the government, and can more effectively eliminate insurgents, provide security, and gather intelligence.3 Information obtained from local partners is often bound to local and cultural processes and is difficult for outsiders to obtain.4 Our study sought to fill key literature gaps and further unpack the causal relationship between working with local partners and counterinsurgency success.

Why and how should counterinsurgency forces select local partners?

Hazelton et al. (2017) found that local partners are critical to counterinsurgency success if they have control over the public. Other sources find that without access to the public, local partners will not have information on insurgent locations and activities.

Local partners that target rivals can hinder counterinsurgency efforts by increasing insurgency recruitment. Sectarian partners, poor civil-security force relations, and partners that commit civilian atrocities can increase insurgent support.

Should shared goals be considered in the selection of local partners?

Local partners whose long-term goals diverge from the long-term goals of the counterinsurgency force can prevent success. Branch & Wood (2010) explain local partners should believe in the counterinsurgency’s goals, stating partners with divergent goals are subject to corruption and unauthorized violence.

Elias (2018) challenges the view that shared goals are essential for local partner-counterinsurgency force cooperation. Their quantitative study found diverging interests do not reduce local partner cooperation, and instead found the dependence between counterinsurgency forces and partners to be the critical factor driving local partner cooperation. Our study assesses this relationship causally.

Literature also suggests local partners can be useful to counterinsurgency forces, but simultaneously harmful to long-term counterinsurgency success.5 For example, “tribal entrepreneurs” increased the legitimacy of the Kazari government in Afghanistan, but there were no effective control measures in place to prevent them from abusing their power. They ultimately engaged in predatory behavior, negatively impact the counterinsurgency effort.

Literature controversy: should service provision be directed at building state legitimacy or providing short-term security?

Counterinsurgency forces can provide services to reduce insurgent violence.6 One framework emphasizes that assistance by counterinsurgency forces can lead to success when the assistance provides for civilians’ immediate security needs. Local partners should be the focus of development aid, according to this framework, because local partners are effective providers of security.

A second framework emphasizes assistance by counterinsurgency forces should be used to improve host government capacity. In this framework, service provision achieves long-term success by building state legitimacy.7 Several studies also indicate the importance of providing assistance to local partners selectively to ensure assistance contributes to the short- or long-term goals of the counterinsurgency rather than the independent goals of local partners.8

METHODOLOGY

Our study employed a qualitative research methodology to investigate the role local partners play in counterinsurgency. We also sought to build off Elias (2018)’s quantitative study of dependency by assessing the causal relationship between local partner/counterinsurgency force dependence and counterinsurgency success. To meet these objectives, we employed a mixed-methodology study, including an analytical case study of the Anbar Awakening and structured interviews with professionals experienced in counterinsurgency policy challenges.

FINDINGS: An analytical case study of the Anbar Awakening

The Al-Anbar province in Iraq was the heart of the Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) insurgency. Tribal leaders initially had an “alliance of convenience” with AQI, but AQI ignored local customs, and was widely disliked among locals.9 During the Anbar Awakening10, local Sunni tribes cooperated with the United States and coalition forces because tribal leaders began to perceive that their goals were more in line with the US’ goals than AQI’s goals11. Iraqi tribes eventually organized to expel AQI12.

Prior to the Anbar Awakening, tribal leaders in Al-Anbar province did not cooperate with counterinsurgency forces. To Sunni tribal leaders, the United States desired to occupy and “de-Sunnify Iraq”.13 As a result, many Sunnis supported AQI and joined the insurgency.14 To combat this, US forces bolstered local partner control over civilians by helping Sunni Sheiks reduce the flow of recruits from their tribes to AQI. The sheiks then were able to convince sub-tribal leaders and ultimately their tribes to reject al-Qaeda15, prompting many Sunnis to stop providing intelligence, support, and recruits to AQI.

It was only after Tribal leaders were convinced the United States did not seek to “de-Sunnify” Iraq that they were willing to work with the US against AQI. This demonstrates that if local partners believe their existence will be jeopardized by the counterinsurgency (in this case, Sunni tribal leaders thought their existence was jeopardized by the US desire to “de-Sunnify” Iraq), they will not work with counterinsurgency forces. The Anbar Awakening illustrates the importance of local partner and counterinsurgency force goals that are not in diametric opposition.

The Anbar Awakening also shows the importance of trust in fostering local partners/counterinsurgency force cooperation. Even if individual Sunni tribes found it advantageous to align with the US against al-Qaeda prior to the Anbar Awakening, they were unable to trust the US would follow through with its promises. The US decision to follow through with its commitment to work with Sheikh Abdul Sattar in 2006 built necessary trust that laid the foundation for cooperation between Sunni tribal leaders and the US during the Anbar Awakening.16

FINDINGS: Interview evidence

We found that local partners are essential for counterinsurgency success.17 Local partners allow counterinsurgency forces to maintain a smaller, in-country presence, contribute local expertise, and provide access critical intelligence.

Local partners allow counterinsurgents to have a limited, in-country presence

Adding to existing literature, our findings suggest working with local partners can lead to counterinsurgency success because local partners allow counterinsurgency forces to have a limited presence. This is beneficial because it prevents the United States from being considered a “hostile occupying force”.18 Citing the importance of a minimal presence in Iraq after the Al-Askari bombing, a US Army Special Forces Lt. Colonel (ret) claimed he had only seen [counterinsurgency] success when local partners were the public face and when US forces “stayed in the shadows”, quietly training and advising the host-nation. A policy research analyst also explained the US used local partners to avoid a larger military footprint in Afghanistan.19

Local partners contribute cultural expertise

Consistent with existing literature, we found local partners are critical to counterinsurgency success by providing cultural and language support and regional expertise. According to a US Navy CTI, host nation partners can provide expertise in “a region of the world that we don’t learn a lot about in the American education system.”

Local knowledge is critical, a US Army Special Forces Lt. Colonel explained in an interview, because local partners lacking in cultural knowledge can inadvertently disrupt local processes. This is consistent with the findings from the interview with a Retired Command Sergeant Major, who explained local partners have a greater stake in outcomes than foreign partners.

Local partners can access critical intelligence with or without access to the population

Consistent with existing literature, we found local partners contribute to counterinsurgency success by providing intelligence. The Lt. Colonel explained that, when training a Jungle Brigade in Northern Ecuador, he taught them how to use the public to become a “massive intelligence source against the opposition”. A Command Sergeant Major (ret) we interviewed explained that local partners are the only way to influence the population, and that working with locals increases intelligence flow to counterinsurgency forces.

Our research critically builds upon existing findings by explaining that corrupt and unpopular local partners can also provide intelligence that contributes to short-term success, but that they can simultaneously prevent members of the population from supporting the counterinsurgency and providing long-term support. The analyst noted local partners can provide intelligence even when the local partner is unpopular with the public. In Afghanistan, US forces relied on unpopular, corrupt warlords for local intelligence. Our research critically finds that corrupt and unpopular local partners can contribute to intelligence necessary for short-term success, but they often limit public, long-term support for the counterinsurgency forces.20

Shared long-term goals can support long-term, counterinsurgency success, but are not necessary to achieve short-term success. Shared short-term goals are necessary to reliably achieve counterinsurgency success.

Like our case study on the Anbar Awakening, our interview evidence shows shared goals are important to achieving counterinsurgency success. Consistent with existing literature, we found shared, long-term goals can support overall counterinsurgency success. Our research provides a more nuanced definition of “shared goals” by finding that shared, long-term goals are not necessary to achieve short-term success, but that without shared, long-term goals, local partners may prevent the counterinsurgency force from fully achieving their long-term goals.

We also found shared, short-term goals are necessary to reliably achieve short- or long-term counterinsurgency success. In Afghanistan, for example, local partners with divergent short-term goals provided the United States with false intelligence, causing the US to attack the partners’ local enemies instead of al-Qaeda.21

Working with sectarian, local partners can undermine counterinsurgency success at both the short- and long-term levels because sectarians may have different, short-term goals from counterinsurgency forces. Sectarian, local partners have used counterinsurgency force resources to target their local rivals instead of the insurgents, which undermined short-term, counterinsurgency success. Counterinsurgency forces should recognize the increased risk of working with sectarian partners, even to achieve short-term success. Sectarian partners also threaten long-term success. According to the policy research analyst, relying on sectarian, local partners impacted Afghan perceptions of the US, and threatened the legitimacy of the Afghan government.

While working with partners with shared, short-term goals but different long-term goals can negatively impact long-term counterinsurgency success22, working with these partners is often essential. In addition to providing intelligence, local partners can also provide force protection and security23 critical to achieving short-term objectives. The policy research analyst explained that, in the early 2000s, the United States’ short-term goals in Afghanistan aligned with the short-term goals of local partners (fighting the Taliban and eliminating terrorists). The US successfully worked with local partners to achieve short-term counterinsurgency success.24

When working with a local partner that does not share the long-term goals of counterinsurgency forces, the policy researcher suggested incorporating the local partner in a way that does not undermine the long-term goal of building and sustaining a government. Although our findings support the idea that local partners with different, desired political end states are sometimes necessary to achieve short-term success, we found divergence in long-term goals between local partners and counterinsurgency forces limits the long-term possibilities for counterinsurgency success. We found local partners that best support short- and long-term counterinsurgency objectives align with both the long-term and short-term goals of the counterinsurgency force.

Dependency: Building off the work by Elias (2018).

We found if the counterinsurgency force is dependent on the local partner for short-term success, it is difficult to use leverage over them to get them to align with the counterinsurgency force’s long-term goals. In Afghanistan, corruption was antithetical to the long-term goal of a legitimate government. Decreasing local partner corruption required accountability, but it was more important for the United States to achieve immediate, short-term goals, such as force protection, than to demand accountability from the local partner providing that security.

We found from our interview with the policy analyst that demanding accountability is more difficult at the lower levels, where the local partner is necessary for essential, short-term tasks, including force protection. Demanding accountability from higher levels is often more successful. For example, in Afghanistan, the Karzai government would rotate provincial governors if a governor in an area of importance was corrupt. However, the policy analyst suggests this would often cause corruption to be relocated to another province rather than eliminated. Often, counterinsurgency forces must live with corruption and subsequently, reduced success in achieving political goals, when working with local partners with divergent, political goals.

Trust is critical for local partner-counterinsurgent relations

Our interview finding that trust is critical for positive relations between local partners and counterinsurgency forces supports our findings from the Anbar Awakening case study and findings from Kristoffersen (2012). The US Army Cryptological linguist explains that language training and shared dangers and struggles are essential to build trust between counterinsurgency forces and local partners. The Retired Command Sergeant Major emphasized the importance of long-term presence and commitment in building trust between local partners and counterinsurgency forces.

Service provision reduces violence by improving state legitimacy

We build upon existing literature surrounding security provision, finding that capacity-building services improve trust in the host government, but that the public must first be provided security. We found working with local partners that were ineffective at providing security for civilians can negate the positive effects of service provision25 and subsequent public belief in government.26 Counterinsurgency forces that are working with violent local partners must be aware that these partners may be negating the positive effects from capacity-building service provision on host government trust and legitimacy.

Our findings support Shapiro & Felter (2011)’s finding that the ultimate goal of service provision, after security has been provided, is to improve state legitimacy, and suggest that this is the mechanism by which services reduce violence. The policy analyst explained that the goal of service provision is to provide the public with necessities and economic opportunities more effectively than the insurgent elements. This improves local government capacity and subsequently, public trust that the government will provide for them.

Conclusion: Our findings build off existing literature and provide essential information on the importance and selection of local partners. This information is critically important for policymakers-- if an ill-fitting local partner is selected, counterinsurgency could fail, leading to further violence and regional instability affecting US and coalition forces or civilians.

Note: Emily’s newsletter piece is a condensed version of a larger research report. If you would like to read the full piece, email me at ebarbarossa@middlebury.edu.

Image Credits:

GERSTEIN, ABBY PHILLIP and JOSH. “Fannie Mae On Donilon's Résumé.” POLITICO, 9 Oct. 2010, https://www.politico.com/story/2010/10/fannie-mae-on-donilons-resume-043348.

Image of Tom Donilon with President Barack Obama, 2010.

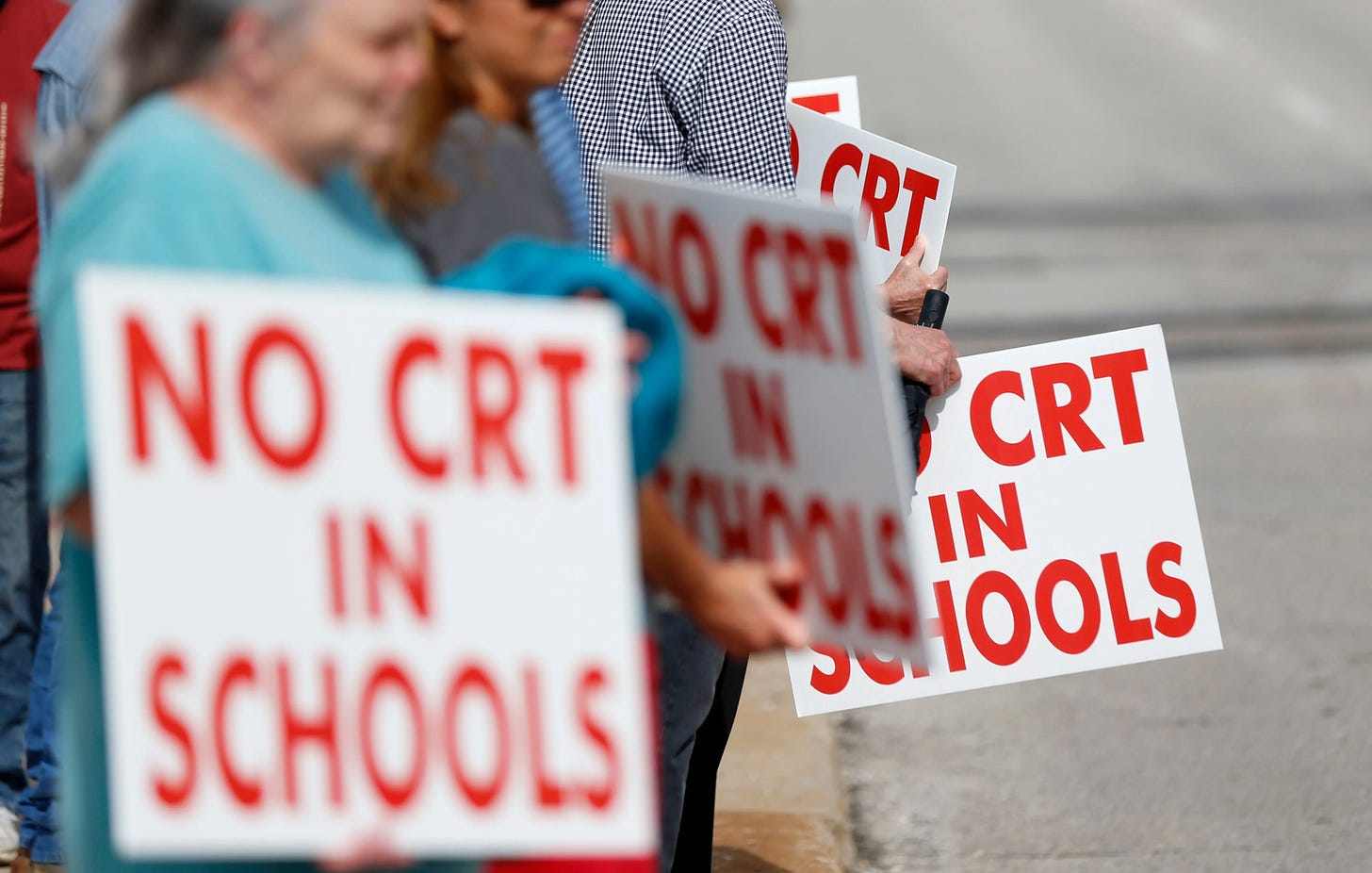

Richards, Erin, and Alia Wong. “Parents Want Kids to Learn about Ongoing Effects of Slavery – but Not Critical Race Theory. They're the Same Thing.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 10 Sept. 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2021/09/10/crt-schools-education-racism-slavery-poll/5772418001/.

Image by Nathan Papes, Springfield News-leader/USA Today Network

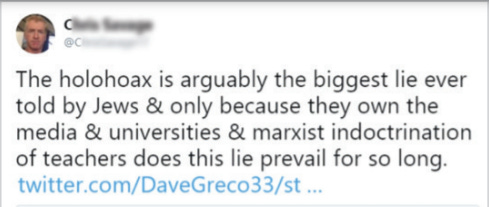

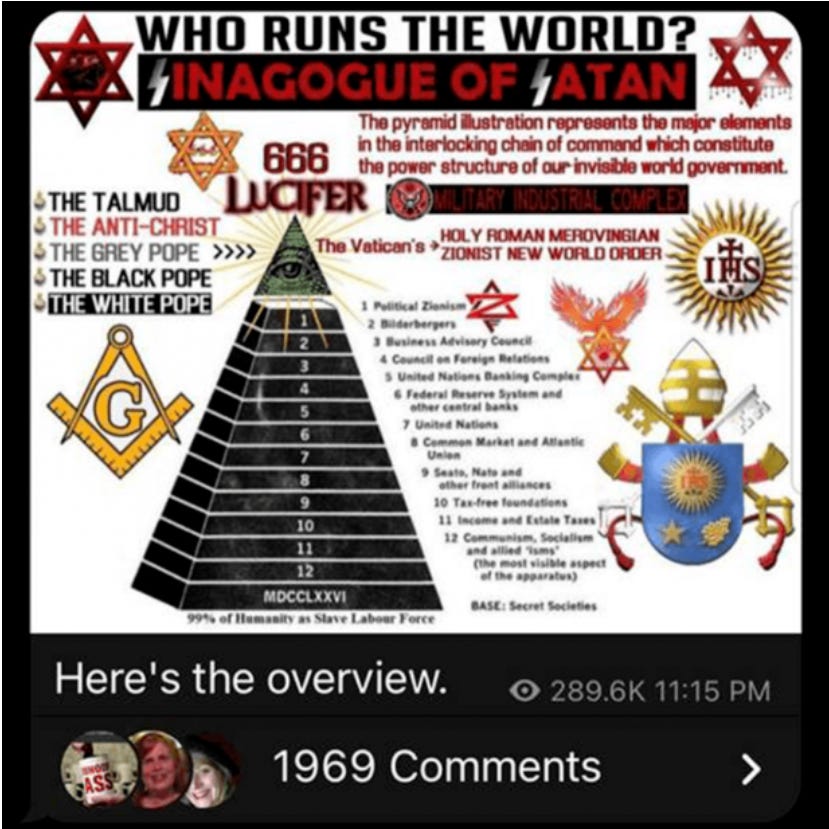

Anti-Defamation League, https://www.adl.org/.

Images of anti-Semitic tweets/

For the purposes of this paper, we define local partners as local elites or organizations with societal power

Branch, D., & Wood, E. J. (2010). Revisiting Counterinsurgency. Politics & Society, 38(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329209357880;

Corum, J. S. (2006). TRAINING INDIGENOUS FORCES IN COUNTERINSURGENCY:: A TALE OF TWO INSURGENCIES. Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College. http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep11838;

Ucko, D. H. (2013). Beyond Clear-Hold-Build: Rethinking Local-Level Counterinsurgency after Afghanistan. Contemporary Security Policy, 34(3), 526–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2013.839258;

Kristoffersen, R. (2012, June). Bleeding for the Village: Success or Failure in the Hands of Local Powerbrokers. Naval Postgraduate School. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA563487.pdf;

Hazelton, J. L. (2017a). The “Hearts and Minds” Fallacy: Violence, Coercion, and Success

in Counterinsurgency Warfare. International Security, 42(1), 80–113.

https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00283;

GREENHILL, K. M., & STANILAND, P. (2007). Ten Ways to Lose at Counterinsurgency. Civil Wars, 9(4), 402–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698240701699623

Byman, D. L. (2006). Friends Like These: Counterinsurgency and the War on Terrorism. International Security, 31(2), 79–115. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2006.31.2.79

Gawthorpe, A. J. (2017). All Counterinsurgency is Local: Counterinsurgency and Rebel

Legitimacy. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 28(4–5), 839–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2017.1322330;

Corum, J. S. (2006). TRAINING INDIGENOUS FORCES IN COUNTERINSURGENCY:: A TALE OF TWO INSURGENCIES. Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College. http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep11838

Katagiri, N. (2011). Winning hearts and minds to lose control: exploring various consequences of popular support in counterinsurgency missions. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 22(1), 170–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2011.546610

Berman, E., & Matanock, A. M. (2015). The Empiricists’ Insurgency. Annual Review of Political Science, 18(1), 443–464. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-082312- 124553;

Ucko, D. H. (2013). Beyond Clear-Hold-Build: Rethinking Local-Level Counterinsurgency after Afghanistan. Contemporary Security Policy, 34(3), 526–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2013.839258

Berman, E., Shapiro, J. N., & Felter, J. H. (2011a). Can Hearts and Minds Be Bought? The Economics of Counterinsurgency in Iraq. Journal of Political Economy, 119(4), 766–819. https://doi.org/10.1086/661983

Branch, D., & Wood, E. J. (2010). Revisiting Counterinsurgency. Politics & Society, 38(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329209357880;

Walter C. Ladwig III, “Influencing Clients in Counterinsurgency: US Involvement in El Salvador's Civil War, 1979–92,” International Security 41, no. 1 (July 2016): 99–146.;

Kristoffersen, R. (2012, June). Bleeding for the Village: Success or Failure in the Hands of Local Powerbrokers. Naval Postgraduate School. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA563487.pdf

Phillips, A. (2009). The Anbar Awakening: Can It Be Exported to Afghanistan? Security Challenges, 5(3), 27-46. Retrieved March 24, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26460092

The Anbar Awakening refers to the 2006 movement of tribal leaders in the Al-Anbar province, Iraq turning against AQI and working with United States forces.

Phillips, A. (2009). The Anbar Awakening: Can It Be Exported to Afghanistan? Security Challenges, 5(3), 27-46. Retrieved March 24, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26460092

Green, D. R. (2010). The Fallujah awakening: a case study in counter-insurgency. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 21(4), 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2010.518860

Phillips, A. (2009). The Anbar Awakening: Can It Be Exported to Afghanistan? Security Challenges, 5(3), 27-46. Retrieved March 24, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26460092;

Al-Jabouri and Jensen (2010) https://www.jstor.org/stable/26469091?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

McCary (2009): The Anbar Awakening: An alliance of Incentives https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01636600802544905?src=recsys

Green, D. R. (2010). The Fallujah awakening: a case study in counter-insurgency. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 21(4), 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2010.518860

Al-Jabouri and Jensen (2010) https://www.jstor.org/stable/26469091?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Interview with a Retired Command Sergeant Major with significant experience with counterinsurgency in Latin America

Interview with US Army Cryptological Linguist

Interview with policy research analyst specializing in Afghanistan

Ibid.

Ibid.

Interview with the Retired Command Sergeant Major; Interview with policy research analyst

Ibid.

Interview with policy research analyst specializing in Afghanistan

Interview with a General Officer

Interview with policy analyst